Key Takeaways:

- Digital twins create virtual replicas of packaging lines, enabling simulation of job flows, layouts, and control strategies.

- Converters use simulations to evaluate the impact of different job sequences, changeover strategies, and staffing scenarios on throughput.

- Digital twins support virtual commissioning of new equipment, reducing ramp-up time and disruption during installation.

- Predictive models within the twin environment help forecast maintenance needs and performance degradation.

- The technology provides a data-backed foundation for capital expenditure decisions and long-term capacity planning.

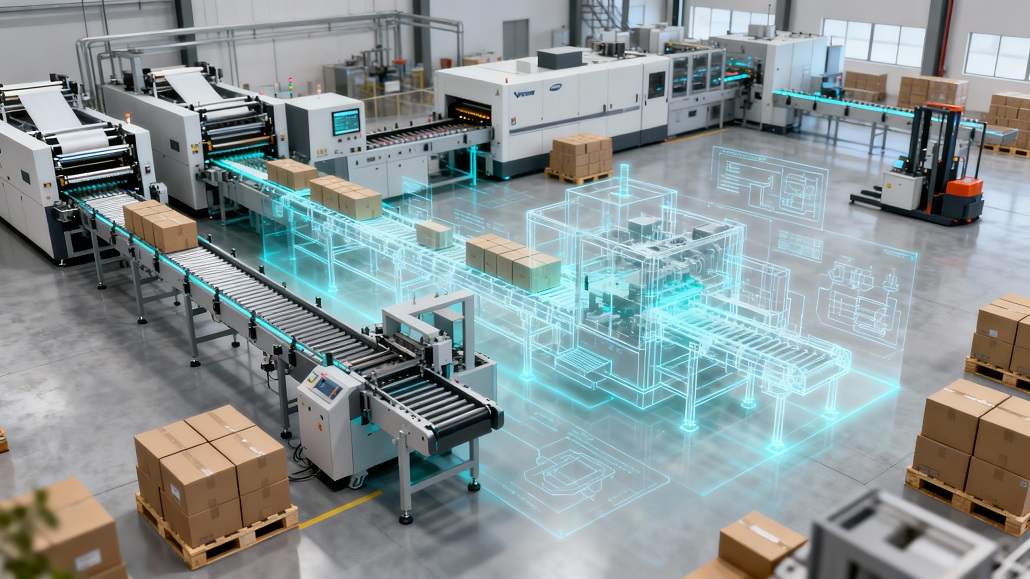

As packaging plants become more complex and capital-intensive, the cost of trial-and-error decision-making on the shop floor has grown significantly. Changing line layouts, introducing new presses, or experimenting with different job sequencing strategies can disrupt operations if they are not carefully planned. Digital twins packaging production technologies are emerging as powerful tools to address this challenge, giving converters a virtual sandbox in which they can test and refine ideas before implementing them in the physical world.

A digital twin is a dynamic digital representation of a physical asset or system, continuously updated with live or historical data from the real environment. In packaging, this might mean a detailed model of an entire folding carton line, a corrugated converting plant, or a mixed fleet of digital and flexographic presses feeding shared finishing resources. Each machine, conveyor, buffer, and inspection system can be modeled within a virtual environment, complete with cycle times, setup durations, and failure modes that mirror reality as closely as needed for decision-making.

One of the most immediate applications of digital twins in packaging is workflow simulation. Production planners can create scenarios that simulate different sequences of jobs, each with unique substrates, formats, and finishing requirements. By running these simulations, they can see how changeovers, cleaning steps, and bottlenecks will play out across the system. For example, they might compare a schedule that groups jobs by substrate to one that groups by ink set or die, measuring the impact on overall throughput and machine utilization. The twin reveals queuing behavior, idle times, and downstream congestion that may not be obvious in traditional Gantt charts.

Digital twins also support layout optimization. When a plant considers adding a new press or reconfiguring finishing equipment, simulation environments allow engineers to test different floor plans and material flow patterns. They can evaluate how relocating a die‑cutter closer to a specific press affects work-in-process buffers, forklift traffic, and changeover efficiency. This reduces the risk of investing in layout changes that inadvertently create new constraints while trying to solve old ones. It also shortens the time between deciding on a layout and achieving stable production, because many potential issues can be resolved virtually before physical modifications begin.

Virtual commissioning is another powerful application. Instead of waiting until equipment is physically installed to test control logic, sequence of operations, and integration with upstream and downstream systems, engineers can validate these aspects within the digital twin. PLC code, HMI sequences, and interlocks can be run against the simulated line to ensure that equipment responds correctly to start‑up, normal running, and fault conditions. This reduces the number of commissioning iterations needed on site, limiting disruptions and enabling faster ramp‑up to target speeds.

Digital twins packaging production solutions also play a growing role in predictive maintenance. By incorporating wear models, failure probabilities, and historical performance data, the twin can forecast when specific components or modules are likely to degrade below acceptable thresholds. For instance, it can calculate how many additional hours a folder‑glu er can run before a critical bearing is likely to cause unplanned downtime, given actual operating patterns and environmental conditions. Maintenance planners can then schedule interventions at optimal times, avoiding both premature replacement and catastrophic failure.

Press and process optimization add further value layers. Digital twins can simulate how different press settings such as speed, tension, temperature, and curing intensity affect output quality and stability under varying environmental conditions. Converters can experiment with increasing line speeds or reducing setup waste in the virtual environment, observing whether defect rates or energy consumption would rise beyond acceptable limits. They can also model the effect of new ink systems, coatings, or substrates on throughput and curing performance, identifying optimal parameter windows before live trials.

From a strategic standpoint, the ability to simulate capacity scenarios is particularly important. Packaging demand can be highly volatile, influenced by promotions, seasonality, and shifts in customer portfolios. Digital twins allow managers to test “what-if” scenarios such as acquiring a major new account, adding a second shift, or reallocating work between sites. They can observe how these changes would affect lead times, backlog levels, and on-time delivery performance. These insights support more robust capacity planning and capital expenditure decisions, reducing the risk of over‑ or under‑investing.

Building and maintaining digital twins does require investment in data infrastructure and modeling expertise. Accurate simulations depend on high‑quality input data: machine specifications, empirical cycle times, setup durations, and failure patterns. Plants must also establish mechanisms for feeding real operational data back into the twin so it remains synchronized with the physical environment over time. Without this continuous feedback, the model’s predictions would gradually diverge from reality, reducing its value for decision-making.

Another key success factor is aligning the granularity of the twin with its intended use. A highly detailed, component-level model might be appropriate for engineering-level analysis of a single machine’s performance, but unnecessarily complex for high-level capacity planning. Conversely, an overly simplified model may obscure critical constraints or misrepresent interactions between machines. Leading adopters therefore create multiple modeling layers, from plant-wide flow simulations to detailed machine-level twins, each tailored to specific questions and stakeholders.

Change management is just as important as technical deployment. To gain maximum value, operations, planning, and management teams must trust the results produced by the digital twin and be willing to use them in decision-making. Early projects often focus on limited-scope use cases such as validating line layout changes or optimizing a particular job family where results can be compared with actual outcomes and confidence can be built gradually. Over time, as teams see that the twin’s predictions align with the physical world, they become more willing to rely on it for higher-stakes decisions.

Digital twins are also closely linked to broader Industry 4.0 initiatives. When combined with real-time data streams from IoT sensors and MIS systems, they can help create closed-loop control environments where planners and control systems continuously test and refine operating strategies. This convergence supports advanced concepts such as autonomous scheduling, self‑optimizing lines, and integrated supply chain simulations that extend beyond the walls of a single plant.

For packaging converters, the strategic value of digital twins lies in the ability to reduce uncertainty. Instead of guessing how a new line configuration will perform or discovering bottlenecks through costly trial runs, they can explore options virtually and approach implementation with a much clearer risk profile. As the technology matures and becomes easier to deploy, digital twins will likely shift from being experimental projects to standard tools embedded in the way packaging operations are planned, optimized, and expanded.